Apprenticeships: Learning on the Job

In an era in which the college degree is still commonly assumed to be the key to success, a more old-fashioned career path is thriving.

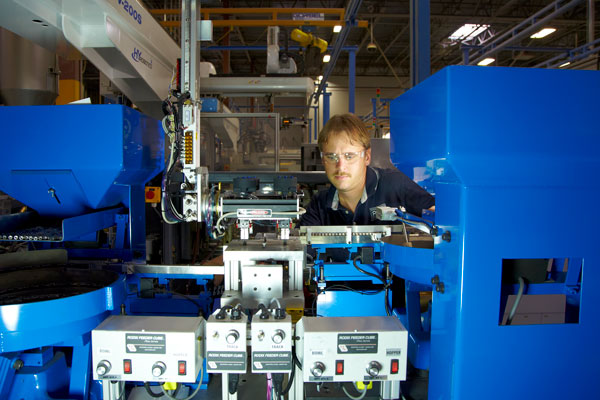

Chief Maintenance Engineer John Getlein, PMT’s first apprentice, at work on the factory floor. (Photo courtesy of Plastic Molding Technology Inc., El Paso)

Since 2013, the number of apprentices working in the U.S. has risen by 42 percent. And in June 2017, President Trump ordered the federal government to expand industry-recognized apprenticeships nationwide by greatly increasing federal funding used to support such programs.

Today, America has more than 22,000 registered apprenticeship programs. In fiscal 2017, according to the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL), more than 530,000 apprentices were at work in federally registered programs. In that year, more than 190,000 individuals entered apprenticeships, and 64,000 participants “graduated” by completing them. More than 2,300 new apprenticeship programs were established nationwide.

Texas currently has about 17,500 apprentices. Almost 40 percent of them are training as electricians, by far the most popular apprentice occupation nationwide.

| Field | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Electrician | 6,234 | 39.0% |

| Plumber | 1,516 | 9.0% |

| Pipe fitter (construction) | 1,330 | 8.0% |

| Sheet metal worker | 663 | 4.0% |

| Structural steel worker (ironworker, structural ironworker) | 658 | 4.0% |

| Elevator constructor/mechanic) | 633 | 4.0% |

| Truck driver (heavy) | 546 | 3.0% |

| Line installer-repairer | 469 | 3.0% |

| Millwright | 401 | 2.5% |

Source: U.S. Department of Labor

One of them, Ashton Chevalier, has finished the first year of a four-year apprenticeship with Gerard Electric in Schertz, near San Antonio. Chevalier, a 21-year-old from Bigfoot in rural Frio County, was working crafts jobs when he decided an apprenticeship was the most affordable way to increase his job prospects.

“It’s a good way to make a living without going broke or getting in debt,” he says.

Companies in many technology industries are hurting for skilled labor. A case in point is Plastic Molding Technology (PMT) Inc. of El Paso. The relatively small firm — with 110 full-time employees and $20 million in gross annual sales — uses plastic injection molding to make customized parts for various industries. PMT moved to El Paso from Connecticut in 2004, its officials say, to supply its customers more efficiently (including many in Mexico) and to take advantage of Texas’ business climate and the North American Free Trade Agreement.

PMT’s shortage of qualified workers, however, has led the firm to create an apprenticeship in “mechatronics” with an emphasis on robotics. Generally, this multi-disciplinary field combines electronics with up to five types of engineering: mechanical, computer, telecommunications, systems and control.

“It’s sorely needed,” says PMT Training Coordinator Mary Sholtis. “It’s hard to find the right person. Our work is very precise.”

PMT’s automation technicians must understand tooling, machine operations and repair, quality assurance and the reading of blueprints. PMT is looking for students in electrical engineering, production and supply chain operations or heating, ventilation and air conditioning — “anyone who’s good hands-on with tools,” Sholtis says. The company wants to collaborate with a technical school and perhaps DOL to develop a unique curriculum for its work-study apprenticeship and pursue grants to defray the firm’s tuition costs.

The apprentice will be paid, Sholtis says, but neither party is obligated to commit to permanent employment upon completion. PMT also hopes to offer apprenticeships in production, toolmaking and quality control in the near future.

PMT’s new apprenticeship is in one of about a thousand career fields offered by some 150,000 employers across the nation. It’s registered with DOL, meaning it meets national standards, has an assigned mentor and will maintain content quality and produce skilled workers. Registered apprenticeships may accept enrollees as young as 16; some require a high school diploma or equivalent. They typically last one to four years, although some can require up to six years. According to DOL, apprentices earn an average starting wage rate of $15 an hour and an average annual salary of $60,000 upon completion. Apprenticeships culminate with portable, nationally recognized, industry-specific credentials; most allow apprentices to earn college credit and even degrees as well.

In Texas, as in about half the states, DOL directly administers the federal program; state agencies do so elsewhere. Apprenticeships are available throughout Texas but are concentrated in Houston, Austin, San Antonio and the Metroplex.

DOL also offers sailors, marines and coast guards the opportunity to improve job skills and complete civilian apprenticeship requirements while on active duty. Almost 90,000 service members participated nationally in 2017.

Registered apprenticeships may be sponsored by individual or groups of employers, labor organizations, educational institutions or industry associations such as Associated Builders and Contractors Inc. (ABC). Its South Texas chapter in San Antonio offers apprenticeships in carpentry, plumbing, electrical and sheet metal work.

ABC lists several advantages to participants, including virtually no cost, paid on-the-job training, professional networking, tax-free stipends, GI Bill benefits for eligible veterans and college credit hours for work/life experience.

Chevalier, an ABC apprentice, describes the electrician training he was “thrown into” as vigorous. “You’ve got to figure it out and learn quick,” he says. “If you don’t pick up on stuff, you won’t make it.”

The work is challenging and demanding. Chevalier has had to monitor a 2 a.m. slab pouring to make sure his electrical lines were okay. Of course, it’s also dangerous.

“I’ve been shocked a few times,” he says, “enough to throw my tools and cuss a little bit.”

Once he attains journeyman status, Chevalier plans to pursue the master level and eventually run his own business.

Apprenticeship often is touted as a key to closing America’s widening industrial workforce “skills gap.” But apprentices are nothing new at PMT. Twenty years ago it trained its first, a maintenance worker named John Getlein. He’s still on the payroll — as the chief maintenance engineer.

“He’s one of our best employees,” Sholtis says. FN