The Treasury Operations Division Keeping Tabs on Texas' Bottom Line

Money comes in — from state agencies, taxpayers and the public — in the form of fees, services and taxes. And money goes out — for payroll, vendor payments, tax refunds and the state’s investments. Nearly all the state’s money flows through the Texas State Treasury.

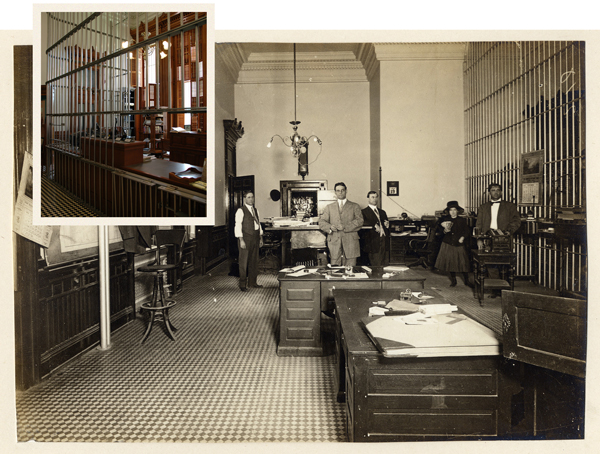

The original Treasury office in the State Capitol, seen in operation and as restored today.

Photo courtesy of the Archives and Information Services Devision, Texas State Library and Archives Commission

The business of state government involves millions of transactions and billions of dollars, and the Comptroller’s Treasury Operations Division safeguards and accounts for them all. The division has been an arm of the Comptroller’s office since the mid-1990s, but a part of Texas history since 1845, when the new state established the elected office of state treasurer. (Visitors to the south side of the Texas Capitol can see the treasurer’s business office, complete with teller windows, restored to its original 1900 appearance.)

The Texas Treasury has a long and colorful history, including an 1865 robbery of $17,000 in silver and gold bars after the collapse of the Confederacy, and the 1909 delivery of nearly $2 million in cash and gold — about $52 million in current dollars — in a single, heavily guarded express train. Perhaps most notable, however, is that the final state treasurer, Martha Whitehead, ran on a campaign promising to eliminate her own job as a money-saving measure, and to merge Treasury operations with the Comptroller’s office. She succeeded and, after a constitutional amendment, the Treasury became part of the Comptroller’s office in 1996.

Four Treasury teams

Today, nearly 50 employees staff the Treasury and work with a variety of customers, both in person and electronically.

“Most of our customers are state agencies, but we also interact with businesses and individuals who either receive or pay money to the state,” explains Tom Smelker, Treasury Operations director. “We staff a teller window at our office for anyone who wants to cash a state warrant, and to accept deposits from state agencies. Citizens and businesses can also pay us electronically. Our TexNet website [an electronic payment system for certain Texas taxpayers] processes more than $70 billion annually, and we process all electronic and credit card payments for the Texas.gov website.”

Treasury Operations comprises four business areas that execute the state’s financial transactions.

The first stop for nearly all incoming deposits, returns and disbursements (requests for warrants from other state agencies) is the Banking and Electronic Processing group. Checks that come in are immediately deposited electronically; the days of Treasury staff delivering them to a bank for deposit are long gone. This group reconciles state warrants and checks; tracks and researches warrant information for state agencies, banks and other entities; and deposits money received from all state agencies.

The Cash and Securities Management team oversees funds transfer, tracks incoming federal funds, makes major payments (such as those for state employee salaries) and determines the daily amount of cash available for state investments. The team also works with other agencies to ensure funds are available through various electronic systems.

To monitor the ever-changing financial and regulatory environment, the Public Finance group ensures that the state remains in good standing with the financial markets. This team manages the state’s cash flow, issues Tax and Revenue Anticipation Notes (TRANs), short-term debt instruments used to manage temporary cash flow problems, and registers bonds issued by the state and Texas local governments (thus deeming them legally valid and enforceable).

Finally, the Treasury Accounting team reconciles the state’s cash assets on a daily basis. The group accounts for cash transactions posted to all state agencies and all money deposited or invested in approved financial institutions, collects interest on state investments and determines how to allocate the interest appropriately. In fiscal 2016, Treasury Accounting reconciled more than 500 state bank accounts about 12,000 times.

Open government

The Comptroller’s commitment to transparency and open government includes Treasury-related data. For example, Treasury Operations allocates money from a pool of funds so the Comptroller’s investment entity, the Texas Treasury Safekeeping Trust Company, can invest them. These funds, collectively known as the “Treasury Pool,” are invested in a mixture of vehicles, earning some returns while providing a high level of liquidity (ready access to funds). Texans can access information about these funds and their rates of return on the Comptroller’s website.

The division’s quarterly Bond Appendix provides a general description of state finances, including historical data and trends, the Treasury balance and current investments. This information is updated on the Comptroller’s website around the 10th of each February, May, August and November.

Similarly, the division’s quarterly Cash Flow Report shows the state’s available cash and compares projected and actual cash positions by quarter and fiscal year.

Treasury Operations by the Numbers

In fiscal 2016, Treasury Operations:

- processed 1,100 checks per minute during peak periods

- collected $125 billion in receipts

- processed transactions with up to 1,000 financial institutions each day

- supported the financial operations of 200 state agencies

The golden age

Concerning the 2017 legislative session, Smelker reports few hot-button issues, “other than some programs that wanted the freedom to collect and spend money without Treasury oversight and controls. This can result in mismanagement or misuse of the state’s money, so we don’t recommend it.”

The 2015 session, however, brought an exciting development for a division that usually operates quietly in the background. “Last session we became involved in legislation to establish a state-managed depository for storing precious metals such as gold and silver,” Smelker says.

Gov. Greg Abbott signed the Texas Bullion Depository bill into law on June 12, 2015, officially establishing the first state-authorized precious metals bullion depository in the nation (HB 483, 84th Legislature). Before the legislation passed, Smelker had twice been called upon to evaluate the Comptroller’s role in a potential depository, both in the 2013 and 2015 sessions.

On June 12, 2017, Comptroller Glenn Hegar announced Smelker would be the administrator of the depository, bringing nearly 30 years of Treasury service to his new role.

True Texas: The Great Treasury Robbery

The robbery of the Texas State Treasury on June 11, 1865, is one of the boldest crimes in Texas history, and remains unsolved.

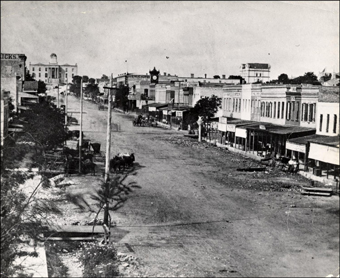

The end of the Civil War plunged Austin into a state of chaos. Law enforcement all but disappeared and Union occupation forces had not yet arrived. A small band of 30 volunteers, organized under former Confederate Captain George R. Freeman, tried to quell a mob that had seized control of downtown Austin, looting stores and wreaking havoc.

Scene of the crime: Congress Avenue, sometime before 1875.

Photo courtesy of the Austin History Center

But while Freeman and his volunteers were able to restore order to Austin, they were unable to defend the State Treasury from armed bandits, despite a tip that the robbery was imminent.

Freeman gathered his men at a church at the southern end of Congress Avenue and proceeded to the Treasury building, then located just northeast of the Capitol, where they found a group of 30 to 50 (eyewitness accounts vary) participating in the break-in. A brief gunfight ensued; one raider was mortally wounded but the rest escaped, heading west toward Mount Bonnell.

Freeman, realizing his men were outnumbered and outgunned, decided not to give chase immediately, opting instead to lead a posse the next day that found nothing except a few coins dropped by the robbers in flight.

The bandits made off with more than half of the Treasury’s gold and silver reserves, worth about $17,000 at the time. They’d used pickaxes to enter several free-standing safes, but failed to breach the Treasury vault.

None were ever captured; their wounded ally died soon after the incident. The stolen loot (worth more than $270,000 today) has never been found, making the Great Treasury Robbery of 1865 one of Texas’ coldest unsolved cases.

Stewards of the state’s dollars

In September 2016, the Treasury celebrated its 20th anniversary as part of the Comptroller’s office, and during the recent regular legislative session, the merger and our employees were recognized on the Senate floor with a special resolution.

We’ve got a Warrant for…Your Money

You say check, we say warrant: that’s the terminology Treasury Operations uses when processing funds for other state agencies. Only three state agencies — the Comptroller’s office, the Health and Human Services Commission and the Texas Workforce Commission — are authorized to issue warrants. They work like checks that private businesses and individuals use, but have some differences:

| Warrants | Checks |

|---|---|

| Drawn on the State Treasury | Drawn on banks |

| Payable only by the State Treasury | Payable at any branch location on which the check is drawn |

| Must be negotiated before two years after the close of the fiscal year in which it was issued | Typically “stale” for payment after six months |

| Issued against state agency appropriations | Primarily issued against bank accounts |

| Transaction history must be archived permanently | Banks generally maintain such records for a year or two |

The average tenure of a Treasury employee is 15 years. Seventeen former Texas Treasury Department employees still work at our office. They represent about a third of the Treasury Operations staff, an impressive percentage in an era of career changers. Why have they stayed?

“Many of our employees came from banking backgrounds and enjoy working in a financial processing environment,” Smelker says. “It may be because we combine the best of both government and private industry: the financial environment of a bank and the public service of government. Our staff gets to work with very large sums of money and interact with professionals in the financial world, which is interesting if you like banking.

“We’re a small, close group that has worked well together over the years, and that makes for a good work environment,” he says.

From the gold and silver bars deposited during the 19th century to the electronic exchanges of funds today —and, in a way, coming full circle with the bullion depository — it’s an environment where employees think innovatively, encourage improvements and operate with high accuracy every day. FN

Visit the Comptroller’s website to learn more about Treasury Operations. See Comptroller financial reports online.