Rural Counties Face Hospital Closures The Economics of Medical Care Outside of Cities

Hospitals, alongside other health care facilities, are the backbone of medical care for our population. They are the places people go when things go wrong. But what happens when residents need help and there is no hospital nearby? Or, when there is a hospital, but the nearest specialty care is in the neighboring county?

This is the reality for many rural Texans, with 71 rural counties lacking hospitals. In addition, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) reports 11 counties have no health care facilities, and seven have limited options. (Some of these rely on home health agencies for local nursing and therapeutic care.)

The U.S. health care industry is a vast network of hospitals, general and specialized clinics, insurers, government organizations, private and/or religious care providers, interest groups and patients themselves. All are connected via a financial system driven by questions with a single focus: Who gets money, when and for what? Rural health care facilities face particular financial difficulties: They don’t have highly insured populations to charge for services, and they are more vulnerable to systemic economic pressures and policy changes (PDF).

Addressing these issues requires an innovative approach toward health care in rural areas, says Dr. Kristie Loescher, academic director of the Healthcare Innovation Initiative at the McCombs School of Business at the University of Texas at Austin (UT).

“Until the bigger problems in American health care are fixed, getting care to rural areas will have to be augmented by changes in technology, such as improving access to telehealth and replacing emergency rooms with better medical transport infrastructure,” she says.

Texas Rural Health Care Facilities

Hospitals and clinics are broadly focused health care facilities and typically the most-used sources of primary care. Hospitals can offer inpatient and outpatient care and can house primary care providers as well as provide a large variety of other services. Clinics are smaller, offering only outpatient services, but they also provide a wide variety of services that a primary provider in a hospital might not. The Texas Organization of Rural & Community Hospitals defines a rural hospital as one that exists in a county of 60,000 people or less.

Typical categories of hospitals and clinics found in rural Texas are critical access hospitals, rural health clinics, federally qualified health centers and short-term/prospective payment system (PPS) hospitals, according to the Rural Health Information Hub supported by HRSA and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The PPS is the primary method of Medicare reimbursement (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: Categories of Hospitals, Clinics in Rural Texas

| TYPE | DESCRIPTION | # IN RURAL TEXAS |

|---|---|---|

| Critical Access Hospital | Provides 24/7 emergency care services; 25 or fewer acute inpatient beds | 83 |

| Rural Health Clinic | 50+ percent staff time: Nurse practitioner, physician assistant or certified nurse midwife (as opposed to physician staff) during work hours | 310 |

| Federally Qualified Health Center | Medicare/Medicaid-qualified outpatient clinic | 167 |

| Short Term/PPS Hospital | Provides short stay inpatient services; enrolled in Medicare/Medicaid PPS | 83 |

Sources: Rural Health Information Hub, Texas State Guide (for categorization); HRSA (updated as of Sept. 1, 2022)

Much of the state’s land is rural (83 percent), and the population outside of metros (14 percent) is highly dispersed. North and West Texas, especially, have longer travel times between incidents and health care due to larger-sized counties and a low number of health care facilities. There are 1,750 rural health care facilities (of all types, including nursing, psychiatric and rehabilitative) in Texas to serve 3 million rural residents versus 6,475 metropolitan health care facilities for 26.5 million urban residents. While this averages out favorably for rural areas, it is the distribution, distance and variety of services that are the primary issues.

Rural Health Care Facility Funding

Rural hospitals and clinics in Texas do not have a blanket funding model. Generally, they pay for the cost of their services by billing patients and insurance providers. Rural providers have limited ability to recoup costs from patients and insurers due to underinsurance and low incomes. Most health facilities seek a myriad of funding opportunities.

- Federal Funding

-

A significant portion of rural health facility income comes from federal programs like Medicaid, Medicare and related supplemental assistance programs. Other costs can be covered by supplemental payments such as those created by Texas’ 1115 Medicaid waiver, which paved the way for payments for uncompensated care. This waiver must regularly be approved by the federal government.

- State Funding

-

The County Indigent Health Care Program, funded by county taxes and state assistance, serves as a last resort for those who don’t qualify for Medicaid but are financially eligible. Recipients must establish residency and prove an income at or below 21 percent of the federal poverty level. Counties pay up to $30,000 per resident per year for qualifying services.

- Hospital Districts

-

Some communities vote to form hospital districts to levy property taxes and fund health services within a specified boundary, with limits on the amount by which property tax levies can grow each year without voter approval. Hospital districts also may levy a local sales tax to reduce or buy down property taxes. These taxes cover some health care facility costs, but no district is fully covered from them alone. Also, population declines in some rural areas can reduce tax income. Hospital districts also may receive income from other political subdivisions.

In addition, counties and hospital districts benefit from the state’s Tobacco Settlement Distribution Program, which provides a percentage of proceeds from the state’s tobacco settlement based on reported unreimbursed health care expenses.

- Hospital Partnerships

-

Some rural health facilities keep their doors open through partnerships with larger hospitals (PDF). Urban-based hospital systems may buy rural health centers and direct patients to hubs for specialized care. General health care costs are balanced through revenue for specialized care in the hub.

Economic Pressures

Rural health systems face multiple challenges beyond funding sources. Overall, they have high operating costs, mostly due to the cost of mandatory “standby” services. An emergency room must be available even though rural areas may go days without needing one. Outside of hospital district property taxes and certain sources of supplemental funding, fees are charged when a service is provided.

Nonmandatory clinics provide services beyond general care, such as wound care, obstetrics and gynecology, but they also have upfront costs. If a health care facility can’t pay the overhead, then these services close. According to the Texas Health and Human Services Commission, as of January 2020, at least 20 rural hospitals had stopped inpatient care (PDF), and three were down to emergency services only.

Facilities also face personnel strains due to staff shortages; without primary care providers, rural hospitals and clinics are in greater danger of closing.

Another cost trend is an increase in outpatient versus inpatient care. Outpatient care allows for greater patient turnover, but Medicare and Medicaid historically have subsidized inpatient care more generously.

Impact of Closures

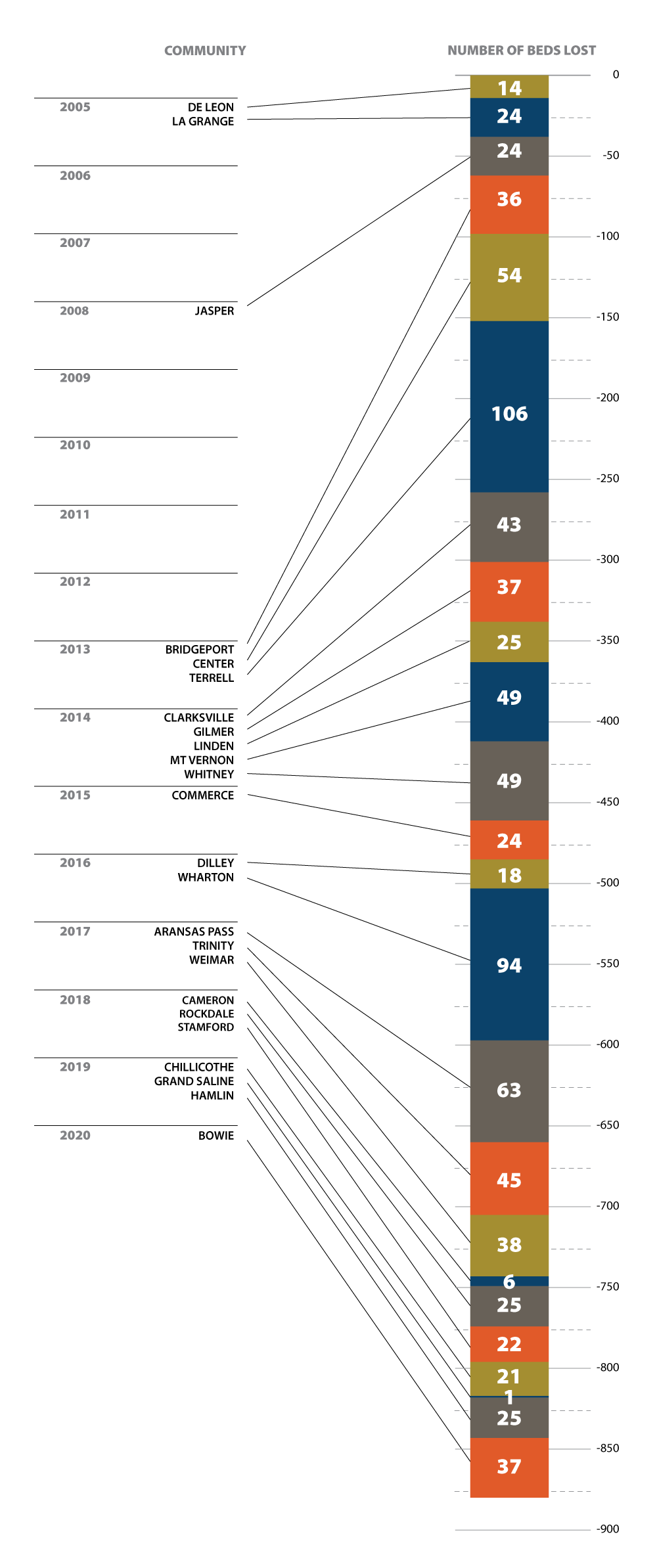

The Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina tracked rural hospital closures from 2005 to 2022, and at 24, Texas logged more than any other state. It is comparable, however, to the national rate per capita (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: Texas Rural Hospital Closures, 2005 to 2022

| Year | Number of Closures | Effected Communities | Number of Beds |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2 | De Leon | 14 |

| La Grange | 24 | ||

| 2008 | 1 | Jasper | 24|

| Total for 2008 | 24 | ||

| 2013 | 3 | Bridgeport | 36 |

| Center | 54 | ||

| Terrell | 106 | ||

| 2014 | 5 | Clarksville | 43 |

| Gilmer | 37 | ||

| Linden | 25 | ||

| Mt Vernon | 49 | ||

| Whitney | 49 | ||

| 2015 | 1Commerce | 24 | |

| 2016 | 2 | Dilley | 18 |

| Wharton | 94 | ||

| 2017 | 3 | Aransas Pass | 63 |

| Trinity | 45 | ||

| Weimar | 38 | ||

| 2018 | 3 | Cameron | 6 |

| Rockdale | 25 | ||

| Stamford | 22 | ||

| 2019 | 3 | Chillicothe | 21 |

| Grand Saline | 1 | ||

| Hamlin | 25 | ||

| 2020 | 1 | Bowie | 37 |

| Grand Total | 24 | 880 | |

Source: The Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research (as of Aug. 11, 2022).

Closures are devastating for communities’ health. A 2019 study on hospital closures saw a rise in inpatient mortality rates of roughly 8.7 percent in rural areas (versus no impact in urban areas) due to an increase in transport time between incident and medical care and related effects.

Moreover, rural health care facilities, particularly hospitals, typically are the largest or second-largest employers in communities. A 2022 study on the economic effects of rural hospital closures found statistically significant downturns in both labor force size and overall population for rural counties when PPS-funded hospitals close.

There have been no Texas rural hospital closures since 2020, according to the Cecil G. Sheps Center (as of Aug. 11, 2022).

COVID-19 Relief and Changes to Medicare

Congress passed legislation in 2020 and 2021 including aid to hospitals responding to COVID-19: the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (March 2020); the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act (March 2020); and the American Rescue Plan Act (March 2021). These funding sources have been available for a limited time for specific expenses.

Albert Ruiz, rural health specialist at the State Office of Rural Health, explains that this funding came with its own set of challenges.

“Some areas received up to $200,000 in federal grant money for COVID response, testing and mitigation. But the requirements for some funding sources involve substantial management, sometimes surpassing the staff’s capacity, especially in rural health clinics,” he says. “They can hire another person to complete the reporting requirements, but that person’s salary will minimize the spending power of the stimuli.” Still, the programs helped rural health clinics by providing funding to combat COVID during the public health emergency.

While pre-planned Medicare payment cuts were paused due to the pandemic, those cuts resumed as of April 2022. The effect on rural health care facilities remains to be seen.

What is the Future of Rural Health in Texas?

Loescher, at UT’s McCombs School of Business, says Australia, with large swaths of rural land like Texas, has implemented telehealth community clinics staffed by nurses or emergency medical technicians who complete intake tasks before the patient meets virtually with a doctor.

In addition, she cites a possible alternative to the infrastructure costs of establishing an emergency room or operating theaters in rural areas: “Having a medical helicopter on standby is perhaps a better use of funds than supporting a brick-and-mortar emergency department since it is cheaper to transport patients quickly to a fully staffed facility.”

Broadband

The 2020 CARES Act included expansion of Medicare coverage for telehealth services so long as the public health emergency declaration remained in place. The latest extension at the time this article was written was through Oct. 13, 2022.

The Broadband Development Office (BDO), operated by the Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, assists with funding and expanding broadband services for the state. Broadband connectivity refers to always-on, high-speed internet access that increasingly has become a requirement for modern life. The Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) benchmark for high-speed internet is at least 25 megabits per second (Mbps) for downloads and 3 Mbps for uploads. According to the 2022 Texas Rural Hospital Survey, one-quarter of rural Texas hospitals subscribe to internet service with download speeds slower than 100 Mbps, which is more common in single-family households. And over one in 20 subscribe to speeds lower than the FCC definition of residential broadband. Of rural Texas hospitals, more than 21 percent say their internet service is not meeting their needs.

More than 38 percent of rural Texas hospitals have said that they are aware of state and federal grants that would help them pay for broadband costs, which suggests the remaining hospitals are unaware of such opportunities. Expanding and educating more rural Texas hospitals on broadband and the grants available could increase download speeds and help expand the use of telehealth visits. Telehealth visits cut the transportation costs associated with doctor and hospital visits while increasing service through online patient portals for sharing test results or virtual meetings with a care provider.

Efforts to expand broadband may allow rural hospital services to reach more Texans (see text box). But ultimately policymakers, health experts and rural health staff will play key roles in meeting ongoing challenges to continue providing health care in rural areas. These experts must strategize expansion of health access to areas that are lacking to maintain and sustain the health of rural Texans. FN

Nursing shortages are being seen across all types of health care facilities. Read about some of the efforts to increase the number of nurses in our April issue of Fiscal Notes.